Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, have long been used in consumer products to provide resistance to heat, oil, stains, grease and water. But they became the focus of regulatory scrutiny once it became clear how persistent they are in the environment — a persistence that earned them the moniker “forever chemicals” — and the adverse effects they can have on human health.

Such scrutiny is about to increase even further. Recently proposed federal PFAS regulations are stricter than and will supersede existing state-level regulations, which cannot be less stringent than those at the federal level. They will designate PFAS as hazardous substances and require public drinking water utilities, or water systems, to monitor and treat PFAS levels in addition to compelling responsible parties to remediate any contaminated sites over the long term.

To address those future regulations, an increasing number of customers are proactively developing mitigation strategies. In the meantime, demand for PFAS services — and related spending — is expected to soar.

A history of limited regulation

In the U.S., regulation of PFAS has been limited up until very recently. They were not included in the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) until 2012, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) only proposed a legal limit to their presence in drinking water in 2023. Before that, the agency limited its actions to issuing nonenforceable health advisories.

Meanwhile, with the help of public pressure and advocacy groups, state and local governments have largely been driving the regulation of PFAS. State regulatory agencies have the authority to enforce such regulations — 10 states currently have enforceable PFAS drinking water limits — or to adopt guidance/notification levels, which 13 states have done to date.

But a combination of an improved understanding of the impact of PFAS on human health, a greater level of authority granted to the EPA by way of some recently passed laws together with numerous laws already on the books (e.g., Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), SDWA, National Defense Authorization Act), and increased political and social pressure has prompted the agency to propose stricter regulations.

Two major changes on deck

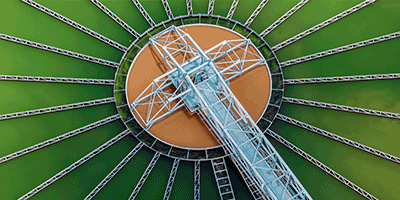

Upcoming regulations stemming from previously passed laws would require that two core things take place: one, that water systems monitor and treat PFAS levels in drinking water; and two, that parties responsible for contaminated sites would have to remediate the sites in question (see Figure 1).