Transition towards a more sustainable business model presents companies with great opportunities for value creation and can be a source of competitive advantage, while those who lack actionable plans risk falling behind their peers. L.E.K. Consulting’s 2023 Decarbonisation Survey found that leaders and organisations are strongly committed to decarbonisation, as global warming intensifies and pressure to adapt continues from customers, investors and regulators. Nowadays, sustainability is a top boardroom priority, with 63% of businesses surveyed having established net-zero goals. At L.E.K., we use the experience and expertise of our Sustainability Centre of Excellence to help our clients design their strategies and identify opportunities for differentiation and value creation.

Many companies struggle to create comprehensive plans operationalising their sustainability strategy. In a recent project, we worked for the distribution business unit of an auto original equipment manufacturer (OEM) which had committed to net-zero objectives and had designed a strategy but was falling short, with only 30% of the objectives supported by identified and validated initiatives. In our diagnosis, we uncovered that it suffered from a silo effect where each function focused solely on its responsibilities, neglecting interdependencies with others. We also discovered that transforming initiatives were being set aside, as they were perceived as creating too much uncertainty and adding short-term costs. As a result, not everyone in the company had the same understanding of the strategic objectives, resulting in engagement levels that were highly heterogeneous between various functions.

This example, as well as many others, illustrates the need for a comprehensive corporate transformation to achieve decarbonisation. Having set the strategy and the ambition, it is essential to design the transition end to end with sufficient detail.

Operationalising decarbonisation

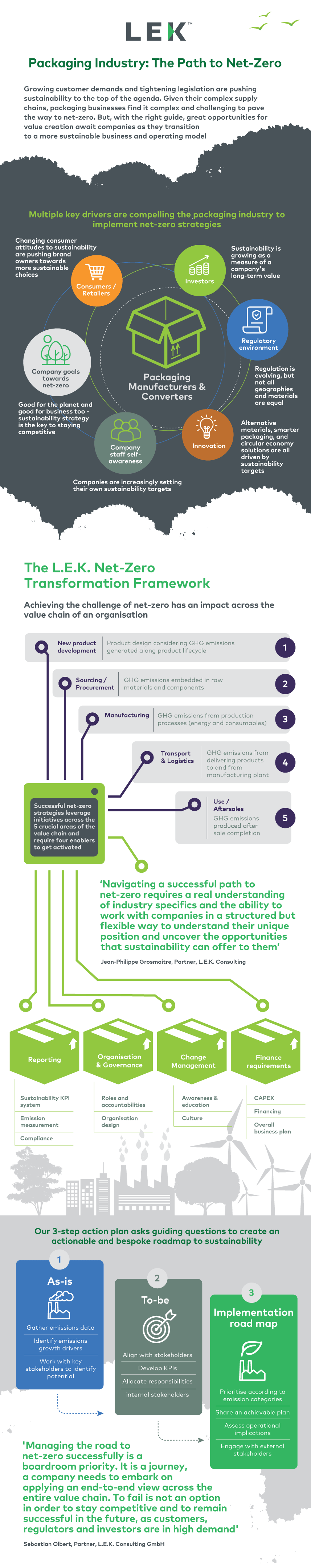

When looking at the environmental impact of a product, experts consider all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across the life cycle of the product, from the cradle to the grave. Similarly, a company seeking to operationalise its road to decarbonisation should look at all its functions along the value chain, from product development to after sales.

Re-engineering the product to reduce GHG emissions

New product design is a crucial area with great improvement potential, especially through consideration of circular business models. First, material usage can be minimised by modular design and multifunctionality, leveraging digitalization (3D design) to eliminate unnecessary material while still meeting specifications. Second, designing easily disassembled, repairable and recycled products will be key to reducing material usage. Third, the use of sustainable materials in the product conception is building momentum as a means of reducing the GHG emission footprint.

Other aspects can be leveraged at the product development stage, such as optimising energy efficiency through low-energy production processes, seeking constant feedback from manufacturing to reduce waste in a lean approach, optimising the product and its packaging to maximise space utilisation, or designing lighter-weight products to make transportation more efficient. Finally, product conception significantly influences emissions during use (e.g. energy savings features such as sleep mode, smart technology for better control and remote monitoring).

Reshaping sourcing and procurement to optimise upstream emissions and adapt to low emission products

In line with development, the sourcing and procurement function has a key role in finding and operating with sustainable raw materials, including the procurement of recycled materials (recycled high-density polyethylene, recycled aluminium, etc.). This entails traceability and labelling of suppliers and monitoring of Scope 3 GHG emissions evolution. Ensuring suppliers implement energy-efficient policies, improve their own material efficiencies and track their own emissions is also key.

However, this won’t suffice for sourcing and procurement. Suppliers require more visibility into their workload to invest in their transition. Partnerships could offer a solution, working with preferred and more advanced suppliers willing to make the necessary effort to help reduce their clients’ GHG emissions. Procurement teams could even consider co-development of products, aligning R&D to reduce overall emissions. Finally, this function will need to optimise transportation routes for sourced goods and even require low emission transportation wherever possible.

Manufacturing: the low- and the high-hanging fruit

Manufacturing levers to operationalise decarbonisation mainly fall into two categories. The first involves regular process optimisation that saves costs and emissions — this is the low-hanging fruit. This is the day to day of any manufacturing executive and creates opportunities for net cost savings that will pay for other GHG emissions reductions; examples are improvements in yield, waste reduction, recycling and energy frugality (e.g. reducing off-time energy consumption) within the plant. In addition, manufacturing 4.0 initiatives represent a meaningful source of marginal savings, creating additional efficiencies through better analytics, digitalization and automation.

These savings can fund additional decarbonisation levers that require expenditure, increasing the overall cost base only marginally, such as switching to alternative cleaner energy sources or creating additional efficiencies on utilities with more electrification. Throughout our client experience, we have capitalised on different types of processes (dealing with energy for production, consumables, manufacturing equipment engineering and maintenance, production waste) to support quick wins in the decarbonisation of manufacturing.

The second category, the ‘high-hanging fruit’, demands significant capex and has many uncertainties linked to the maturity of new technologies. With the transition underway, many industrial strategies (with their capex plans) can become quickly obsolete and even strategically misleading if they don’t consider market and regulatory changes. In their search for the right and most competitive process with low/no GHG emissions, companies should adapt their industrial strategy in three ways. First, extend the lifespan of current equipment (at the expense of temporary higher maintenance and refurbishment costs) to overcome uncertainties relating to still-immature replacement technologies in terms of performance and return on investment. Second, look at any new meaningful and necessary capex under the GHG angle to ensure that it optimises for emissions reduction. Third, partner with key equipment providers for priority access to key process innovation, which can create a competitive advantage on low-no emission. In some industries, this collaboration might extend to consortium or even industrywide levels.

To decarbonise, many industries must make substantial footprint changes, which requires transformational capex much beyond previous levels. As a result, industrial strategic planning will have to be reinforced, to find the best options in terms of footprint evolution and to document business cases to convince governance and investors, and to work with regulators and sector players to set a new level playing field.

Transport and logistics, a world of accessible opportunities

As most of the logistics costs rely on energy consumption, optimising transport efficiency directly impacts GHG emissions. Many operational levers are already mature, including route optimisation software, GPS enabled logistics efficiencies and green logistics policies (sea/rail vs road, electrical last mile, biofuels, etc.). While some levers remain uncertain and for the medium to long term (such as sustainable aviation fuels or green hydrogen), companies must eventually adapt their transport mix (and therefore cost) to the success or failure of these alternatives.

Companies should also optimise packaging and storage to mitigate GHG emissions in logistics. In packaging, prevention will be key to avoid unnecessary consumption; reuse will impact the volume of new purchases; recycling will reduce the cost of sourcing; and energy recovery will offer additional options for cost and GHG reduction. In storage, leveraging new technologies and data will be key to optimise utilisation and therefore footprint. For example, artificial intelligence applied to digital twins of logistics systems will help in identifying further optimisations beyond current practices.

Back-office functions: a question of change and culture to contribute to the collective effort

This category of corporate GHG emissions is the closest to end-consumer GHG emissions, as it covers both services and people, who commute daily and travel for work; use office materials, heat and power; and consume food. These areas have many identified levers such as carpooling, public transport or shuttles for commuting, reduced paper usage, energy-efficient equipment, energy-efficient heating and air conditioning systems, renewable energies, composting, and sorting waste, among many others. Operationalising GHG emissions reduction in this context is particularly a question of change and culture, requiring strong leadership.

Use and after sales: a key area in contact with clients

Scope 3 GHG emissions also relate to the usage of a company’s product until the end of the value chain.

Many customer engagement initiatives are possible, including educational materials and social media to promote sustainable use of products. Maintenance services often offer emissions reduction potential with the leverage of remote monitoring and self-diagnostic technologies. After sales spare parts management can benefit from logistics-related GHG reduction strategies such as sustainable transport, consolidated shipments or packaging optimisation.

Dealing with product end of life is also crucial, emphasising the need for clear recycling instructions and take-back programs. Progress has been made, but further improvements are necessary, including clear labelling on the product for recycling and repair guidance.

As illustrated by the examples above, all functions of an organisation need to be involved to operationalise the company’s decarbonisation strategy; a value chain approach is pivotal. At L.E.K. we have established a database of initiatives, enabling us to rapidly identify what might be missing and to ponder options for hard-to-abate emissions.

On our projects, we have found a few recurring difficulties which are slowing down if not neutralising many initiatives. Interdependencies between functions or with external stakeholders create many challenges. Additionally, most functions experience talent scarcity and find it hard to dedicate skilled resources to these additional projects. Finally, we have found that there is often a problem of rhythm; similar to the law of diminishing returns, companies put energy into delivering short-term results but find it hard to continue investing on initiatives paying off in the medium to long term, even though these initiatives can be game-changing.

Designing a full-fledged transformation program for decarbonisation

We are convinced that walking the talk on decarbonisation requires a full-fledged transformation program. The development of a successful decarbonisation strategy follows a three-step action plan consisting of the required ‘as is’ analysis, the design of the ‘to be’ solution and the derivation of an ‘implementation roadmap’. To activate the developed decarbonisation strategy, it is of ultimate importance to design a transformation program which guides the evolution of the operating model across the value chain, phases the process and coordinates decarbonisation initiatives.

In such a transformation program, a central team provides transformation pace, rhythm and tools to workstreams; manages interdependencies; ensures problem-solving escalation; democratises best practices; and consolidates progress to ensure global consistency according to strategic direction.

Because operationalising decarbonisation strategy involves many moving parts with key decisions such as capex, we have found it useful to develop a digital twin of the business with sufficient granularity to establish both the financial and emission impacts of envisaged initiatives, based on different options.

Lastly, effective change management is crucial for this type of transformation. Not only key stakeholders, but also all employees need to engage and adapt the way they work in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment. Gathering their input, feedback and ideas fosters ownership and empowerment among those impacted. This means providing financial and talent resources to support the change program — together with training, tools and necessary support systems — is a crucial requirement to ensure a smooth transition.

Conclusion

Transforming the company to operationalise its decarbonisation strategy requires a full-fledged program that will ensure structured coordination, adequate pace, explicit trade-offs and, ultimately, a consolidated vision of progress, while empowering all stakeholders with the resources necessary to change the way they work and engage.

Please contact the L.E.K. Consulting Sustainability Centre of Excellence to find out more about our work helping organisations operationalise decarbonisation.

L.E.K. Consulting is a registered trademark of L.E.K. Consulting. All other products and brands mentioned in this document are properties of their respective owners. © 2023 L.E.K. Consulting