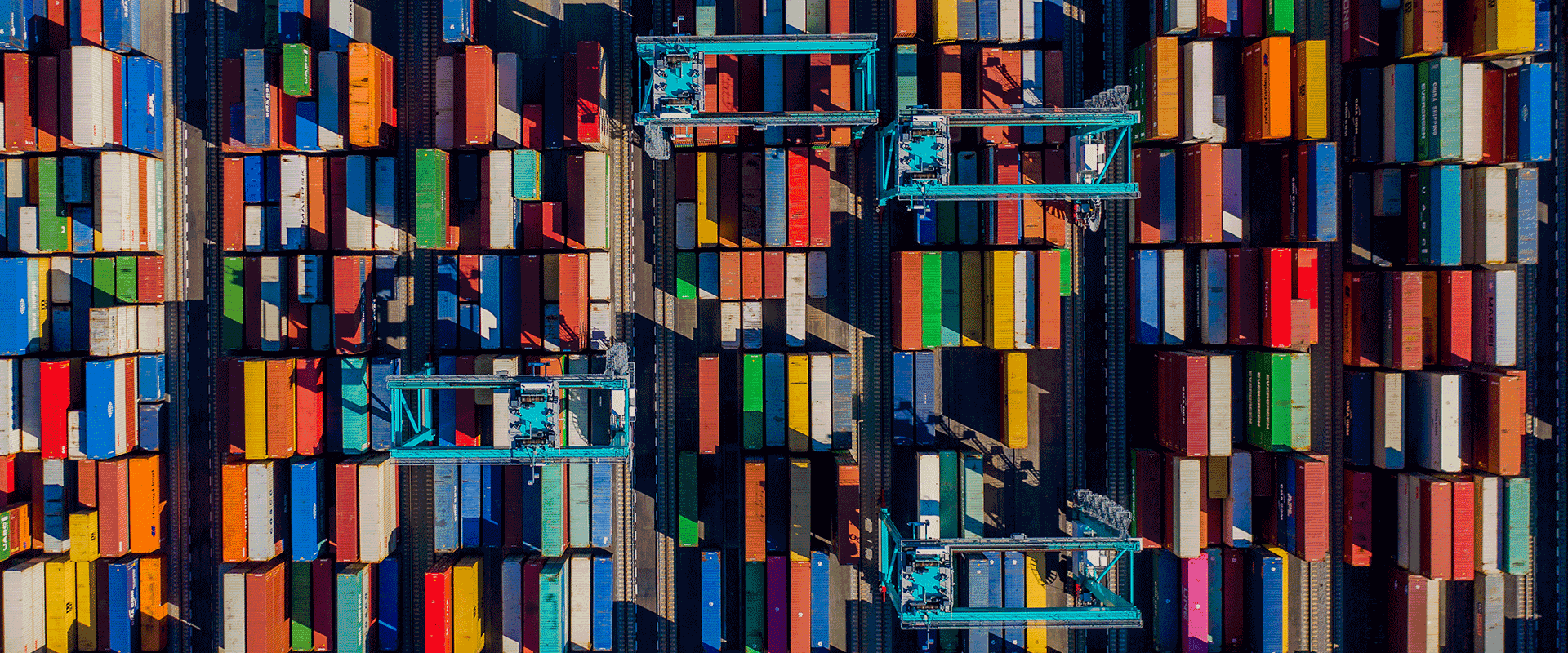

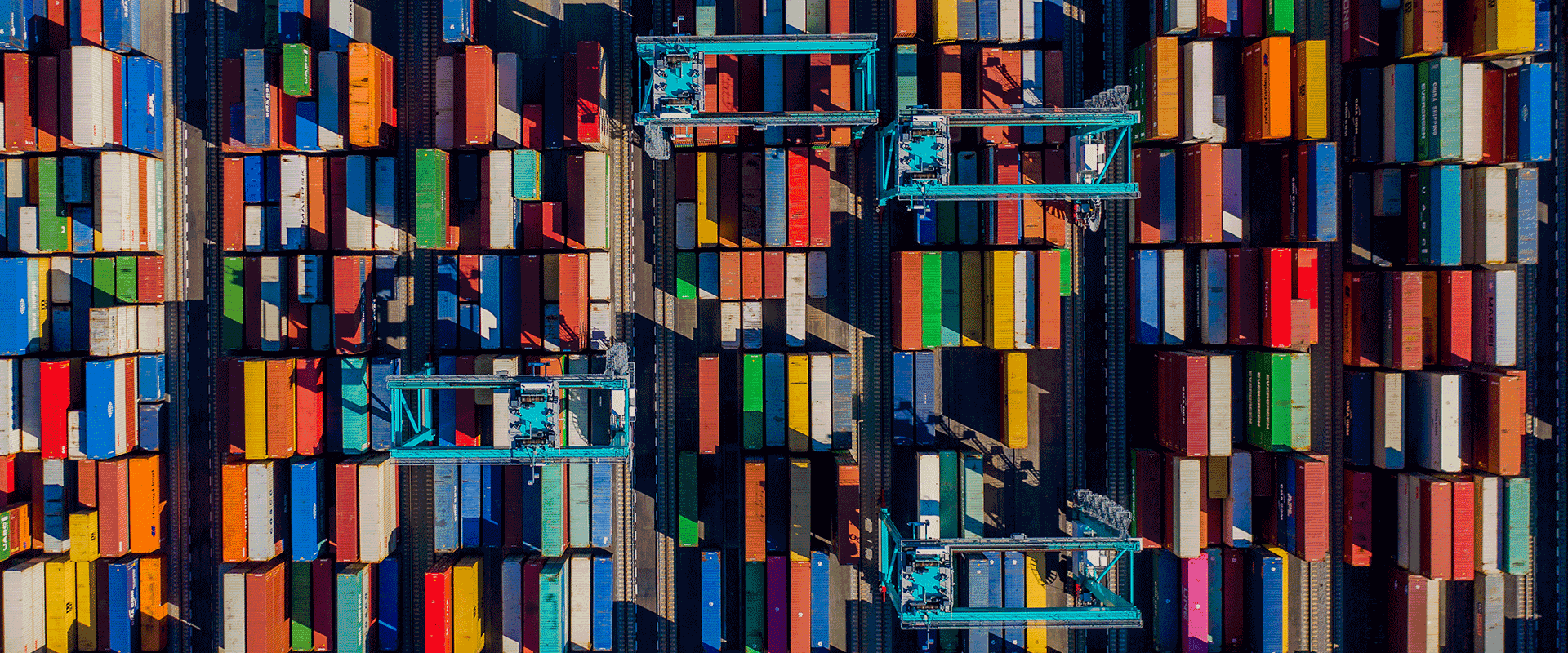

How Supply Chain Participants Can Weather the Disruption in 2022

- Article

The U.S. supply chain has become overburdened in recent months, especially for imported goods, resulting in congested ports and warehouses, longer-than-usual wait times and an unprecedented increase in freight rates. While these problems are rooted in systemic issues around American labor and port infrastructure, sharp changes to carrier capacity and consumer demand during various stages of the COVID-19 pandemic have only made the situation worse. And there’s a real possibility such prolonged wait times will continue through 2022 — and perhaps even beyond to 2023.

Multiple factors impact shipping congestion — and by extension, freight spot rates — across the supply chain: the degree of demand for imported goods through shipping routes, logistics worker capacity (and any outcomes from their labor union agreements), the availability of critical logistics infrastructure, the capacity of carriers in the global fleet and, finally, any intervention taken by the U.S. government.

In the current climate, demand for imported goods through shipping routes has increased considerably. There is also a critical shortage of port workers (e.g., drayage drivers, crane operators) and truck drivers to turn ships and clear congestion; chassis and other critical logistics infrastructure are insufficient as well. Shipping carriers ordered a record number of vessels in 2021 to create additional capacity, but that will only begin to be realized in 2023. Meanwhile, in late 2021, the Biden administration announced a shift to 24-hour operations at many major ports and is considering further action to reduce congestion.

While some market participants believe the current port congestion will be short-lived, others are less optimistic and see it taking more than a year to resolve. In a base case, we expect the freight spot rate environment to stabilize in 2022 as robust demand continues into the new year and congestion at U.S. ports starts to ease in the third and fourth quarters. However, if demand for imports falls in the face of high inflation, causing congestion to ease earlier in the first or second quarter, spot rates will decline as well. But if economic conditions improve further and demand increases, spot rates will rise and congestion won’t ease until sometime in mid-2023 (see Figure 1).

Manufacturers, retailers or any company that is reliant on overseas markets for inputs shouldn’t wait to see how the supply chain situation shakes out. Rather, they should consider taking the following steps to ameliorate its impacts now and better prepare themselves to manage additional disruptions down the road.

Ongoing tensions with China — including tariffs, the threat of a trade war and COVID-19 — are already forcing companies to evaluate alternatives to Chinese manufacturing.

Diversifying manufacturing will likely be a long, costly process and involve many stakeholders. There are significant barriers to finding other sources of supply, among them a lack of scale, suboptimal transportation infrastructure and the time it takes to establish new supplier networks and logistics capabilities. But doing so will not just reduce risk; given the ability to leverage lower labor costs in attractive geographies that have been investing in infrastructure, such as Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, it could reduce exposure to tariffs and improve cost efficiencies, too.

Such a strategy will be industry specific. Certain industries deemed critical to national security, such as semiconductor or medical supplies manufacturing, are already accelerating the onshoring of their products.

In order to reduce costs, retailers have taken a “lean” approach to inventory in recent years. But with no clear end in sight to the current supply chain disruptions, it’s time to reassess that strategy.

Holding inventory is expensive, and many companies believe they will likely return inventories to pre-COVID-19 levels when trading conditions normalize. However, each company must analyze the risk/return trade-off between this cost against the cost of being unable to fulfill demand during a disruption.

Supply chain visibility is still in its relative infancy, and the lack of a unified view makes it hard to proactively plan for disruptions and delays. What’s needed is transparency across the entire supply chain enabled by platforms that present a single, unified view. Manufacturers also need clear views into their supplier networks (e.g., Tier 1, Tier 2 suppliers) to ensure production remains on schedule.

Technology can provide visibility into extended supplier ecosystems, allowing companies to obtain more visibility upstream into potential issues, which gives them more time to react. Widespread use of automation can reduce friction for suppliers and participants alike, enabling more-efficient collection and organization of data, in turn generating higher-quality insights.

And digitizing supply chains brings risk management-related benefits beyond pure supply. Mapping out supply networks enables the incorporation of environmental, social and governance-related information such as greenhouse gas emissions, trade embargoes, labor laws and other company policies into supply chain risk management systems, all of which means decision-makers can holistically plan supply chain changes to mitigate against potential risks.

Supply chain disruption will likely be an issue throughout 2022, and possibly beyond. While black swan events of the significance of a global pandemic happen relatively infrequently, adverse events in the form of extreme weather and geopolitical instability continue to occur with more frequency. To weather this current storm and any in the future, companies should avoid dependence on any one manufacturing source, consider buffer inventory and work toward the ongoing digitization of their supply chain. These measures will all come at a cost, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach, but as we have witnessed, an evolution from the status quo is almost certainly required.