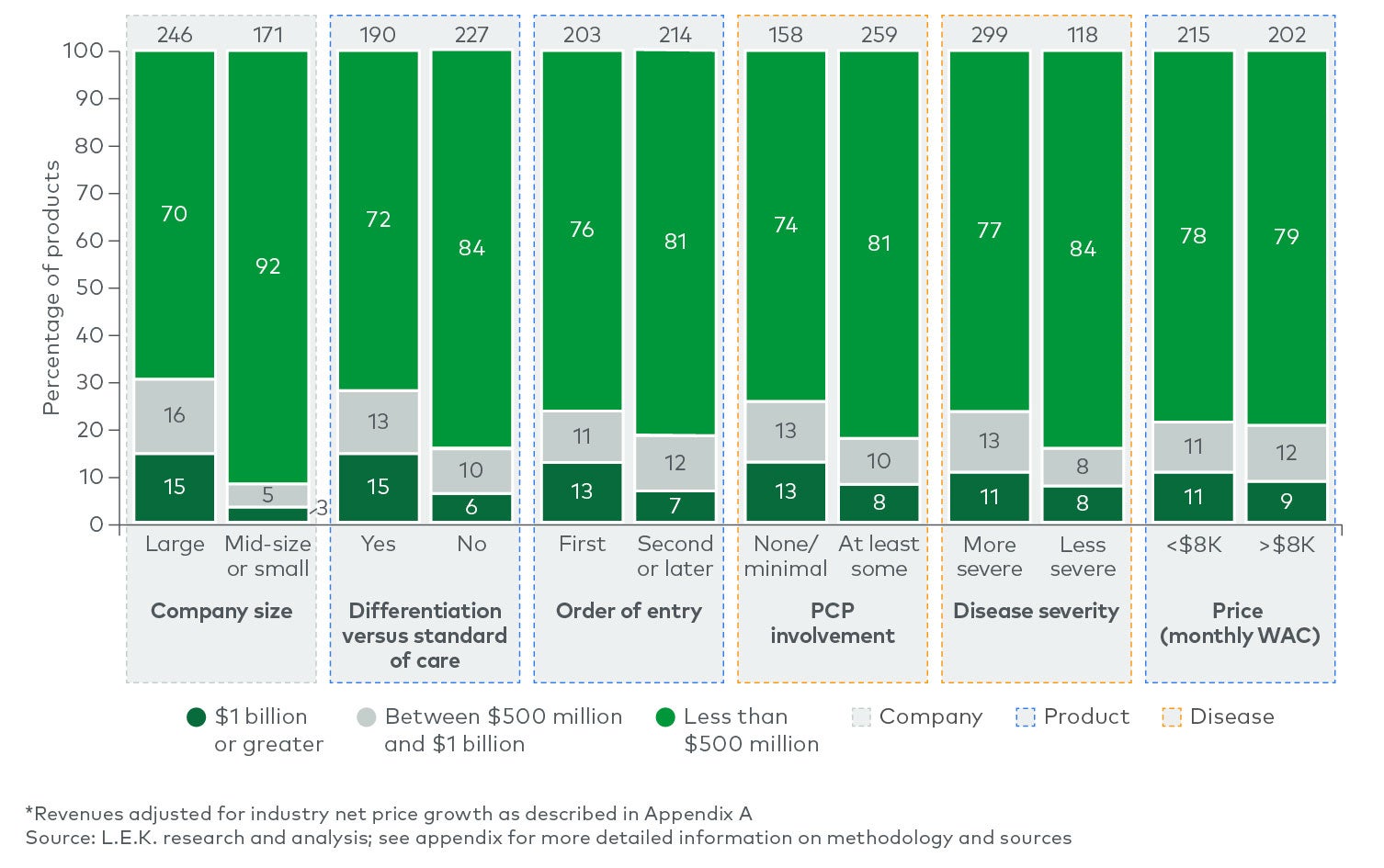

Between 2004 and 2018, more than three-quarters of the products possessed three or fewer predictive attributes, and only 6% of those achieved $1 billion in revenue. Another 20% of the products possessed four predictive attributes, and ~20% of them achieved $1 billion in revenue — more than three times as likely as those with three predictive attributes or fewer. Of the very few products with all five attributes, 45% reached $1 billion. While still no guarantee, having four or more of the five attributes made a product nearly four times more likely to achieve the $1 billion threshold than products with three or fewer attributes. Even at the lower threshold, only products with five attributes had approximately a 64% chance of reaching $500 million at year three. This does not even account for all the technical risk in successfully navigating clinical development.

These findings have broad implications across the product development and commercialization process

These insights have implications for portfolio prioritization, business development, partnering, clinical trial design, and launch planning and execution choices.

-

Portfolio prioritization and business development: Optimizing R&D investments and making business development decisions across multiple assets and/or indications are critical to maximizing ROI. In addition to revenue forecasting and product valuation, companies should consider evaluating programs across the key attributes and recalibrating expectations if products do not meet some of them.

-

Proactive and strategic clinical development: When a company believes it has a product with attractive revenue potential, it needs to invest sufficiently in trials to demonstrate its differentiation from standard of care. It is important to understand which endpoints and performance thresholds will result in meaningful clinical differentiation and then design trials accordingly. This will only become more important as the Inflation Reduction Act is implemented, since clinical differentiation is a critical way to support pricing decisions.

-

Launch planning and execution: Pre-launch activities need to include early engagement with customers to co-develop the product value proposition and its differentiation along the predictive attributes identified in this analysis. Small to midsize companies that plan on self-commercializing need to invest sufficiently in the launch, starting before pivotal trials are designed or at least three years prior to first market authorization. Those that opt for a commercial partnership need to identify the right time in their product’s development to maximize partnership deal terms, while leaving sufficient time to prepare for the launch.

Note: While these findings are specific to the U.S. market, they may also broadly apply to other markets.

If you would like to discuss these findings further, please contact lifesciences@lek.com.